The Atlantic recently published an article that raised a host of eyebrows (and prompted a lot of finger-pointing) because of its alarming title: The Elite College Students who can't read Books. College students unable to read books should be a phrase that can never be true, and yet, according to the article, large numbers of American college students at prestigious institutions either cannot or will not read the books that were once standard fare in the recent past.

Why, then, are college students increasingly unable (or unwilling) to read whole books? Is it the oft-blamed and yet rather vague “school system”? Is it state testing requirements, which test reading and analyzing short passages of text, thus pushing to the side the reading of entire novels or plays? A failing this tremendous—to fail our children in such a fundamental way—rightfully cries out for a remedy. But the question “who is to blame?” doesn’t quite get to the heart of the rot (and make no mistake, the reality that (many) college students aren’t reading books indicates deep and sweeping decay).

Perhaps a question we should also be asking, then, is why? Why don’t we value literature? Why are we not a literary people? Mark Anthony Signorelli asks these questions in his recent piece on the illiteracy crisis:

In what sense are we as a people a literary people? In what sense do we as a people value literature? Who are our great living authors? What have been the great literary events of our lifetime, akin to the Certame Coronario or the mob flooding the docks of New York to get their hands on the latest chapter of “The Old Curiosity Shop?” Does it bother a single American – does it occur to a single American – that there are obviously no answers to these questions?

It is easy to critique the failings of our culture from a comfortable sofa. It is easy to point at school administrations, or those who create state testing requirements, teachers, the students themselves, and even the distraction of smartphones and other devices as culprits of such a staggering problem. But who has the most influence to change the foundation of a culture? Who has the tremendous responsibility to train children to be virtuous men and women who will then, in turn, train their own children? It is the parents. Parents have a duty to pass on to their children their culture and their traditions. It is parents, whether they homeschool or not, who are ultimately responsible for the education of their children.

How, then, can parents foster a love of reading and literature in their children?

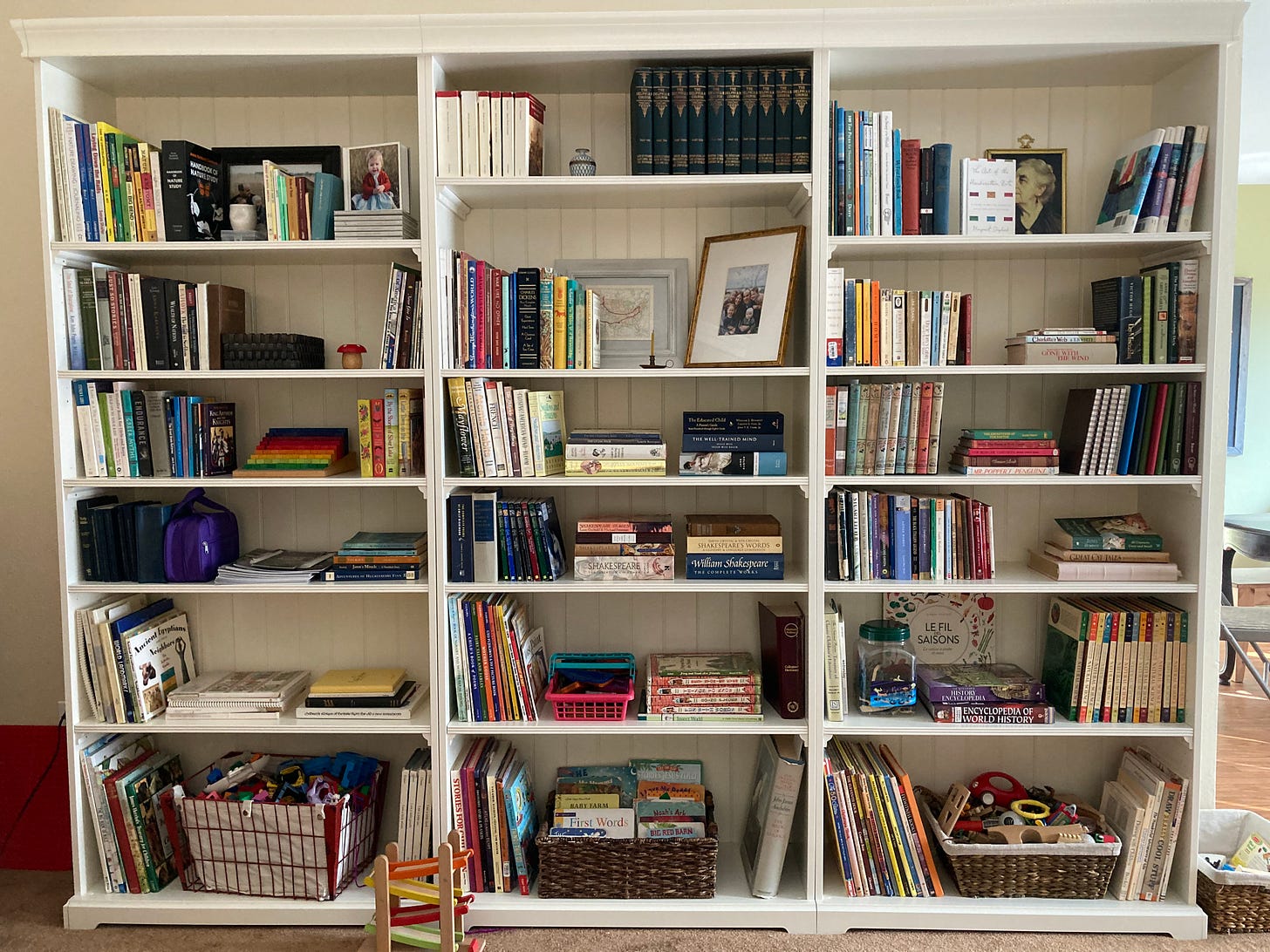

Let your Children see you Read

It is difficult to give our children something we do not have ourselves. Let your kids see you reading (physical) books. How can we expect children to pick up a book if the adults around them never do? Children are taught best by example, not by lecture. Let them see that you love to read; tell them all about what you’re reading with excitement and enthusiasm. Delight and enthusiasm are always infectious.

Read Aloud to your Children

Even (especially!) your teenagers. If you homeschool, this is fairly easy to do. If you don’t, there are still opportunities: evenings, weekends, summer break, etc. All are excellent times for reading out loud, together. As Megan Cox Gurdon wrote in her book The Enchanted Hour, “the act of reading together secures people to one another, creating order and connection, as if we were quilt squares tacked together with threads made of stories.”

One of my fondest memories from all of my (public) school years was during elementary school, when one of the teachers (a Tolkien super-fan; he could write fluently in Elvish!) had the 5th-6th grade children sit on the floor all together while he read aloud The Hobbit. There is a unique magic to reading aloud together with a group. It binds us to one another and the power of the stories we read changes us forever.

No Phones Allowed

When faced with a choice between a) reading a book and b) any device, kids are (nearly) always going to choose the device. Why? Because it’s easier. Reading books is harder than being entertained, so kids (of course!) choose the easier path. This is also true for adults—reading is harder than scrolling, so how do many adults spend their free hours? Scrolling.

This is probably the most difficult (and most important) hurdle to overcome if you want to help your children become readers. So, when you’re reading aloud to your children, put your phone far away from you so it doesn’t become a distraction. If your children have phones, put them in another room so they aren’t tempted to tune out and scroll. If necessary, turn your phone off. And if none of those ideas work, simply unplug the internet for an hour in the evenings so that your family understands that you’re serious. Whatever you have to do—commit to a phone-free environment.

Unplugging your internet for an hour every evening might be a very revealing experiment. Most of us are far more addicted to our phones than we realize.

When I’m trying to start a new habit, it helps me to remember that environment is the invisible hand that shapes human behavior.1 Removing phones from your environment (or unplugging the internet) will make it obvious that reading is a priority for your family, and that you are serious about creating a culture of reading.

Reading is always going to be last on the list of things to do for (most) kids. It’s not flashy, it’s not (obviously) entertaining, and few (if any) of their peers are doing it. It is up to us as parents to show our children that the work of reading is worth every effort!

Reading a good book is like entering a castle and sitting down to a beautifully prepared feast. The feast of reading a good book takes time and effort–it isn’t immediately obvious to a child why reading is so wonderful. The feast has been prepared, and awaits in a beautiful banquet hall, but there are a few heavy iron doors and dimly lit corridors between us and the feast. Perhaps years of neglect have made the door to the castle a bit rusty and hard to open. That’s okay. Open it slowly, with a friend. Perhaps there are many steep stone steps you must climb to get to the feast. That’s okay, too. Take the first few steps up the spiral staircase, however, and the music from the dining hall will grow clearer and more distinct with each step. Once you reach the top of the stairs, the hardest work is behind you. The lush melodies and the aroma of well-prepared food draws you forward until at last you enter the room and your eyes widen upon seeing the long table, laden with more good things to eat than you could ever taste in one sitting.

So it is with our reading lives. The door to the castle may be rusty with neglect. It may take some work to choose to be a literature-loving people. It is hard to start a reading habit (or re-start one), but it is worth it.

The feast awaits.

Keep seeking the virtuous and the lovely,

Shannon

James Clear, Atomic Habits (New York: Avery, 2018), 82.

Absolutely love the feast-in-a-castle metaphor.

I will forever remember being smashed together on the couch with a nursling and all my other littles and piles of books to read at our leisure. Agree with everything in this article. I am saddened by people who don't read books, especially the younger people who will be in places of leadership in our culture. I fear they will be lacking in depth and substance - and joy.